|

|

| Click here for the PF Lyceum Site Index

PF Lyceum Blog #9, march 16, 2006 Carlos S. Alvarado, Ph.D. (For a biography of Dr. Alvarado click here .)  In April of 1935 the New York Times carried an ad stating that Eileen J. Garrett, who established the Parapsychology Foundation in 1951, was going to deliver a lecture in New York City at the Barbizon Plaza on “The Attitude of Modern Science Toward Parapsychology” (Lecture Ad, 1935; see the references at the end). These were the good old days, when the entrance fee for a lecture in New York City was $1.10. But these were also the days when the term parapsychology was first beginning to be used in the United States, not being a common term in English at the time. In April of 1935 the New York Times carried an ad stating that Eileen J. Garrett, who established the Parapsychology Foundation in 1951, was going to deliver a lecture in New York City at the Barbizon Plaza on “The Attitude of Modern Science Toward Parapsychology” (Lecture Ad, 1935; see the references at the end). These were the good old days, when the entrance fee for a lecture in New York City was $1.10. But these were also the days when the term parapsychology was first beginning to be used in the United States, not being a common term in English at the time.

The situation is different today. When I recently searched on the word “parapsychology” in Yahoo, I obtained more than two million hits. The term is now part of our culture, even if it is sometimes used improperly. (On parapsychology and its definitions click here.) While parapsychology designates the scientific and scholarly study of such phenomena as ESP, an early use of the term referred to a delusional system of thought. This may be found in 1887 in the journal Science (Mental Science, 1887). (For excerpts of this article, click here.) Fortunately, others rescued the term from the notion of mere delusions. Later in 1889 German philosopher Max Dessoir (1867-1947) published an article entitled “Die Parapsychologie” in the journal Sphinx. After referring to “extraordinary psychic phenomena,” Dessoir wrote:

It took many years for the term to be used first in Germany and then in Holland to refer to the study of telepathy, mediumship and similar topics. Two journals, the German Zeitschrift für Parapsychologie (since 1926) and the Dutch Tijdschrift voor Parapsychologie (since 1928) also popularized the term in their titles. (For examples of relevant German and Dutch publications click here.)

Some translations from the German presented the term to English speaking readers. A good example were the writings of biologist Hans Driesch (1867-1941). For example, in The Crisis in Psychology (1925), Driesch referred to the “last critical point in modern psychology, namely psychical research or parapsychology” (p. 229).

Other translations from the German in which the term appeared included articles by authors such as Driesch (1927) and physician Albert F. von Schrenck-Notzing (1862-1929; Schrenck-Notzing, 1932). The term, however, was rarely used by English speakers. In fact, the translation of Driesch’s Parapsychologie (1932) did not use the word parapsychology. Instead, following the British tradition, parapsychology was changed to psychical research (Driesch, 1932/1933). The term appeared in the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research during the 1920s but only in summaries of articles taken from the German literature.   While in England and in the United States the term psychical research was used, in France the preferred term was métapsychique (metapsychics). This word was made famous by physiologist Charles Richet (1850-1935) who first used it in his Presidential Address to the Society for Psychical Research to refer to psychical research (Richet, 1905). The term was popularized in later works, the most famous of which was Richet’s extremely influential Traite de métapsychique (1922). Métapsychique was particularly used in France, but also in translation in other European countries, such as Italy, and in Ibero America. While in England and in the United States the term psychical research was used, in France the preferred term was métapsychique (metapsychics). This word was made famous by physiologist Charles Richet (1850-1935) who first used it in his Presidential Address to the Society for Psychical Research to refer to psychical research (Richet, 1905). The term was popularized in later works, the most famous of which was Richet’s extremely influential Traite de métapsychique (1922). Métapsychique was particularly used in France, but also in translation in other European countries, such as Italy, and in Ibero America.

The term parapsychology became more common in English with the work of J. B. Rhine (1895-1980). In his classic work Extra-sensory Perception (1934), Rhine referred to the variety of terms used to designate the field and wrote: “The German usage of ‘parapsychology’ for the general field seems a little more generally appropriate than the others, if we do not use the prefix as implying that psychical research is outside the field of psychology — but simply that it is ‘beside’ psychology in the older and narrower conception” (p. 7). The term parapsychology became more common in English with the work of J. B. Rhine (1895-1980). In his classic work Extra-sensory Perception (1934), Rhine referred to the variety of terms used to designate the field and wrote: “The German usage of ‘parapsychology’ for the general field seems a little more generally appropriate than the others, if we do not use the prefix as implying that psychical research is outside the field of psychology — but simply that it is ‘beside’ psychology in the older and narrower conception” (p. 7).

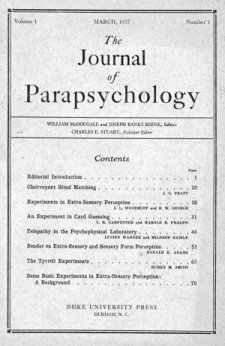

Rhine, and previous German and Dutch writers, used parapsychology as a synonym of psychical research. This, however, started to change. An editorial in the opening issue of the Journal of Parapsychology (JP), published in 1937, started the process. Sometimes attributed to British psychologist William McDougall (1871-1938), but probably authored by Rhine as well, the editorial included the following:

The content of the JP articulated this approach through the experimental reports it published. During its first volumes this consisted of papers on statistically evaluated ESP studies. But while the Journal was influential among some psychical researchers and psychologists in the use of the term, it probably did not affect the general public very much. The popularization of the term in its new meaning came through other publications more accessible to the general public and to other scientists. The JP was discussed both in the journal Science and in the New York Times (Parapsychology, 1937; Scientific Events, 1937). An anonymous writer in the Times said: A rose by any other name may smell as sweet, but when “psychical research” becomes “parapsychology” we no longer pinch our nostrils. We seem to breathe the bracing air of the laboratory rather than the sticky incense of darkened rooms in which frauds hold forth. Yet it would be unfair to the editor of Duke University’s new Journal of Parapsychology to charge them with resorting to a verbal subterfuge in choosing a name. They make it clear in their first number that “psychic research” is an “illogical and unsatisfactory designation” of obscure and inexplicable phenomena that deserve the earnest consideration of scientific men. Parapsychology … is narrower in its scope than psychic research. It is limited to the controlled experimental study of strange divinations and manifestations of mind rather than of the survival of personality after death and of the kind of fortune-telling that passes for spiritualism. In a word, the editors of the journal have wisely decided to follow the lines of least academic resistance. (Parapsychology, 1937)

Although the reference to dark rooms and incense is an obvious exaggeration, the article captures the attempt to create a new discipline, popularizing the new meaning of the word parapsychology. Rhine himself helped to spread the new use of the word. In his first popular book, New Frontiers of the Mind (1937), he told the readers that parapsychology “differs from psychical research in the strictly experimental methods used in its procedure.” This new identity of parapsychology as an experimental science was further publicized, particularly with the general public in a variety of reports about Rhine’s work published in newspapers. While the history of the term parapsychology tends to be forgotten, today it is used with different meanings. Some use it to include any relevant study of psychic phenomena, such as field studies, surveys and experiments (e.g., Wiseman, & Watt, 2005). Others refer to the experimental approach. The latter position sees psychical research as dealing with mediumship and spontaneous phenomena, while parapsychology “has tended to concentrate mainly on relatively modest psychic tasks that can be performed under controlled laboratory conditions with well-defined protocols for data acquisition and processing, and to stay well within the simple statistical models it has helped to define” (Jahn & Dunne, 1987, pp. 45-46). Regardless of what emphasis you decide to give to the term parapsychology, it is important to be aware that the term has a long tradition of being used before Rhine and others redefined it in its experimental sense. It is not incorrect to use it in one way or another. It is just a question of emphasis on different conceptual traditions and literatures. Nonetheless, I must say I find it somewhat peculiar that some feel they have to use psychical research and parapsychology to mean different things. Psychologists refer to their field as psychology, regardless of the time period or methodological emphases. They may talk about qualitative or quantitative studies, experimental or non-experimental approaches, or they may designate areas of study such as child psychology, comparative psychology, physiological psychology, or clinical psychology. But the basic name of the discipline does not change. Just as a term such as psychology can include a variety of conceptual and methodological approaches, so can parapsychology. For some people the issue behind the separation of psychical research (or metapsychics) and parapsychology seems to be the defense of conceptual postures. Those who want to emphasize laboratory approaches, either because of their belief this is a superior approach, or because they want to distance themselves from “embarrassing” mediumistic phenomena, tend to use parapsychology to designate an experimental discipline. Similarly, there are others who use the term in this way because they believe that qualitative studies of gifted individuals and the study of spontaneous cases are the superior approach or because they want to distance themselves from what they believe to be the trivial and reductionistic approaches (and phenomena) of the laboratory. Furthermore, there are some parapsychologists who want to change the name of the discipline to something more neutral than either psychical research or parapsychology, fearing that the historical associations of these terms make life difficult when one applies for grant money or interacts with scientists from other disciplines. Certainly the meaning and associations words evoke are varied, and often, in the ear of the beholder. Driesch, H. (1925). The Crisis in Psychology. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Driesch, H. (1927). Psychical research and philosophy. In C. Murchison (Ed.), The Case For and Against Psychical Belief (pp. 163-178). Worcester, MA: Clark University. Driesch, H. (1932). Parapsychologie: Die Wissenschaft von Den “Okkulten” Erscheinungen. Munchen: F. Bruckmann. Driesch, H. (1933). Psychical Research: The Science of the Super-normal. London: G. Bell. (First published in German 1932) Jahn, R., & Dunne, B. (1987). Margins of Reality: The Role of Consciousness in the Physical World. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. [Lecture ad]. (1935, April 7). New York Times, p. X6. [McDougall, W., & Rhine, J.B.] (1937). Editorial introduction. Journal of Parapsychology, 1, 1-9. Mental science: Para-psychology. (1887). Science, 9, 510-511. Parapsychology. (1937, April 12). New York Times, p. 16. Rhine, J. B. (1934). Extra-sensory Perception. Boston: Boston Society for Psychic Research. Rhine, J. B. (1937). New Frontiers of the Mind. New York: Farrar and Rinehart. Richet, C. (1905). La métapsychique. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, 19, 2-49. Richet, C. (1922). Traité de métapsychique. Paris: Félix Alcan. Schrenck-Notzing, A.F. von. (1932). Scientific events: A journal of “Parapsychology.” (1937). Science, 85, 171-172. Thalbourne, M. A., & Rosenbaum, R. D. (1986). The origin of the word “parapsychology”. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 53, 225-229. Wiseman, R., & Watt, C. (Eds.). (2005). Parapsychology. London: Ashgate International Library of Psychology. Carlos S. Alvarado, Ph.D.

|

|

|

www. parapsychology. org |

||

If we designate something whose scope goes beyond or alongside normal experience with para-, by analogy with words like paragenesis, paragoge, paragraph, paracope, paracusis, paralogism, paranoia, parergon, etc., then we can perhaps refer to those phenomena which do not figure in the normal functioning of the psyche as parapsychic, and to the science which concerns itself with these phenomena as ‘parapsychology.’ ‘Metapsychology’, a similar compound, may be taken as a precedent. The word is not pretty, but in my estimation it has the advantage that it succinctly labels a previously unnamed field halfway between the normal and abnormal, pathological situations, and such neologisms do not, after all, claim more than the limited merit of practical usefulness. (Thalbourne & Rosenbaum, 1986, p. 227)

If we designate something whose scope goes beyond or alongside normal experience with para-, by analogy with words like paragenesis, paragoge, paragraph, paracope, paracusis, paralogism, paranoia, parergon, etc., then we can perhaps refer to those phenomena which do not figure in the normal functioning of the psyche as parapsychic, and to the science which concerns itself with these phenomena as ‘parapsychology.’ ‘Metapsychology’, a similar compound, may be taken as a precedent. The word is not pretty, but in my estimation it has the advantage that it succinctly labels a previously unnamed field halfway between the normal and abnormal, pathological situations, and such neologisms do not, after all, claim more than the limited merit of practical usefulness. (Thalbourne & Rosenbaum, 1986, p. 227) The title of this journal requires a few words of explanation as to how we conceive the relation of parapsychology to psychical research. Parapsychology is a word that comes to us from Germany … We think it may well be adopted into the English language to designate the more strictly experimental part of the whole field implied by psychical research as now pretty generally understood. It is these strictly laboratory studies which most need the atmosphere and conditions to be found only in the universities; and it is these which the universities can most properly promote, leaving the extra-academic groups the still important task of collecting and recording all such reports of phenomena apparently expressive of unusual mental powers as occur spontaneously, obscure warnings and premonitions, veridical phantasms of the living and the dead, and other sporadic manifestations of mysterious origins.

The title of this journal requires a few words of explanation as to how we conceive the relation of parapsychology to psychical research. Parapsychology is a word that comes to us from Germany … We think it may well be adopted into the English language to designate the more strictly experimental part of the whole field implied by psychical research as now pretty generally understood. It is these strictly laboratory studies which most need the atmosphere and conditions to be found only in the universities; and it is these which the universities can most properly promote, leaving the extra-academic groups the still important task of collecting and recording all such reports of phenomena apparently expressive of unusual mental powers as occur spontaneously, obscure warnings and premonitions, veridical phantasms of the living and the dead, and other sporadic manifestations of mysterious origins.